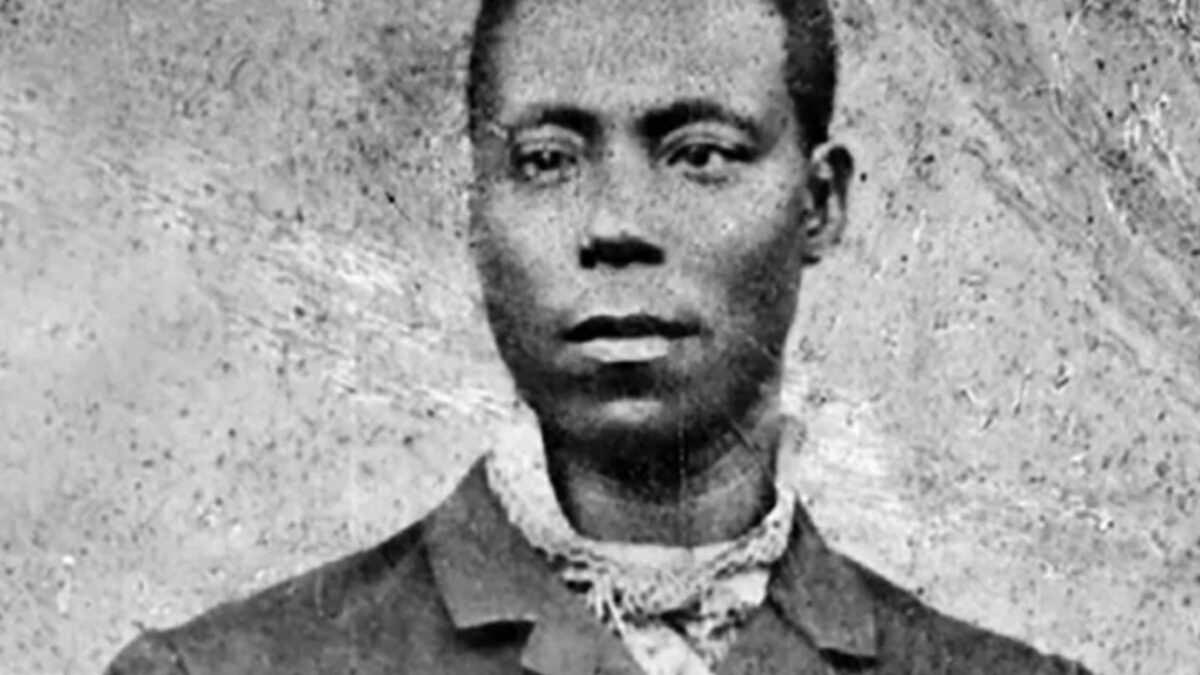

Black History Maker: Thomas L. Jennings

Thomas L. Jennings was born 01 January 1791 in New York to a free Black family. As a youth he learned a trade as a tailor. Many people, not just Blacks, worked as apprentices during this time. That, coupled with the fact that he was a highly skilled tailor adds to the evidence that he worked under a tailor to learn his craft. It’s quite possible that he was self-educated because formal schooling was highly unlikely.

He later met and married a woman named Elizabeth who was born in 1798 as a slave in Delaware. Under New York’s gradual abolition law of 1799, she was converted to the status of an indentured servant and was not eligible for full emancipation until 1827. It freed slave children born after 04 July 1799, but only after they had served “apprenticeships”; 28 years for men and 25 for women. This apprenticeship was far longer than traditional apprenticeships designed to teach a young person a craft. The real reason was to compensate owners for the loss of their “property”.

Mr. Jennings became a tailor in his early 20s and opened a dry-cleaning business in New York City later. While running his business he developed a process called “dry scouring” later known as dry cleaning. He was the first Black man to be granted a patent which took place on 03 March 1821 and he was one of the first to sign an oath declaring himself a citizen of New York. His success set the stage for many other Black inventors to obtain patents for their inventions.

Mr. Jennings’ business expertise and invention of dry cleaning made him wealthy. He used much of his fortune to support the abolitionist movement. Among his countless efforts to end slavery, Jennings was the founder of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia in 1831, and a supporter of the Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned newspaper in the U.S. His children, Matilda, James and Elizabeth were educated, and they all became actively involved in the abolitionist movement as well.

Though free Black Americans, like Mr. Jennings, were able to patent their inventions the process was difficult and expensive. Some Black inventors hid their race while others used their white counterparts as proxies to avoid discrimination even though the language of the patent laws were supposed to be color-blind. If a white person were to infringe on a Black inventor’s patent, it would have been difficult to fight back.

It’s likely that some slave owners secretly patented their slaves’ inventions and on numerous occasions slave owners applied for patents for their slave’s inventions but were denied because no one could take the patent oath — the enslaved inventor was not eligible to hold the patent, and the slave owner was not the inventor. Despite these barriers, Blacks, both free and enslaved still invented or contributed to many technologies at the time, from steamboat propellers to bedsteads to cotton scrapers. Some even made money without patents!

In 1827, he along with several other business leaders were instrumental in establishing “Freedom’s Journal”, the nation’s first African American newspaper. Also, as a champion of the Anti-Colonialization Movement, he addressed the issue head on in a speech he gave before the New York Society for Mutual Relief in 1828. Thomas Jennings dedicated his life fighting for not only Black rights, but Human Rights and many of his family members followed his example.

His eldest son, William, worked for African American publications and was an abolitionist leader in Boston. Another son, Thomas, served on antislavery committees with Frederick Douglass and he was also a renowned dentist and vestryman in New Orleans. Jennings’ wife and daughters were active in the Female Literary Society of New York, which raised funds to free slaves and promote the rights of Black women.

In 1854, his youngest daughter, Elizabeth, won a case that desegregated New York’s public transit system. The Legal Rights Association that he formed to fight for that cause went on to become an early watchdog organization that reported civil rights violations and raised money for lawsuits.

Jennings died in 1859, at the age of 68. Frederick Douglass called Jennings “a bold man of color” who led an “active, earnest and blameless life” in his eulogy. The epitaph on his headstone reads “Defender of Human Rights”.